When pigment meets canvas, those seemingly casual brushstrokes, color blocks, and lines actually follow a set of exquisite “grammatical rules”. These creative languages, known as “painting techniques”, are not only tools for artists to capture the world but also channels for emotions to flow. They are like different dialects, telling various aesthetic stories on the canvas.

Lines are the oldest narrators in painting, carrying the richest emotions with their minimalist forms. The outlining technique is like regular script in calligraphy, defining the boundaries of objects with clear and decisive contour lines. When Wu Daozi painted figures, his brushstrokes were as sharp as swords, and the lines of the clothing folds were as rigid as iron wires, yet they could reveal the softness of silk at the turning points. Da Vinci’s sketches used lines with varying weights to weave the structure of the human body, and each line seemed to come alive, breathing on the paper. The beauty of this technique lies in “controlling the complex with the simple”, awakening the viewer’s complete imagination of the object with the least amount of brushwork.

The texturing technique, on the other hand, is like a prose full of reduplicated words, stacking up natural textures with 细碎 lines. The mountains and rocks in the paintings of Chinese landscape painters, from the softness of “hemp-fiber texturing” to the hardness of “axe-cut texturing”, those crisscrossing short lines are like the wrinkles carved by time on the rocks. When Fan Kuan painted Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, he repeatedly applied dense, raindrop-like texturing strokes, allowing viewers to feel the roughness and thickness of the mountains and rocks. This technique does not pursue similarity in form but firmly grasps the “bone structure” of nature.

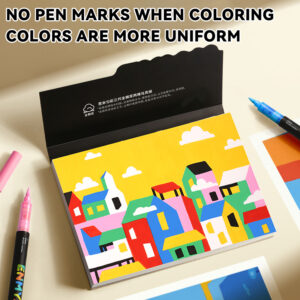

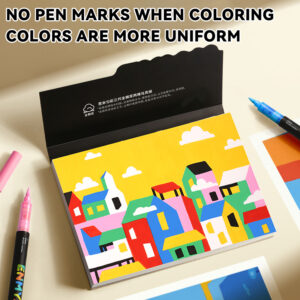

The use of color is the most gorgeous movement in painting, and different techniques 演绎出 different melodies. The flat coloring technique is like a folk ballad, covering the canvas with large blocks of pure colors. Matisse’s cut-out works juxtapose red human figures, blue skies, and green plants, with no transitions or gradients, yet awaken primitive vitality with the most direct color collisions. This technique strips away the interference of light and shadow, allowing colors to return to their pure symbolic meaning, just like the sun in children’s paintings is always golden and the sky is always blue, with a naive stubbornness.

The gradation technique is like a 朦胧 poem, allowing colors to naturally blend on the wet paper. When Chinese meticulous painters paint flower petals, they use clear water to 晕开 the carmine color, making the edges gradually fade into the white paper, as if there is a layer of mist on the petals. The sky in watercolor paintings is the pinnacle of gradation, where cobalt blue and ultramarine slowly penetrate in the wet-on-wet technique, creating cloud-like textures, and viewers seem to be able to smell the freshness of the air after rain. The essence of this technique is “hiding”, making the changes of colors invisible yet delicate everywhere.

The impasto technique is like the brass section in a symphony. Van Gogh’s sunflowers use thick layers of paint to build the curves of the petals, and the traces of the brush are like the chisel marks of a sculpture, casting 细碎 shadows in the sunlight. When viewers walk past the painting, those raised pigments reflect different lusters as the viewing angle changes, giving the flowers a breathing-like movement. The pointillism technique, on the other hand, is a precise chamber music. Seurat arranged countless pure color dots to form the riverbank and the crowd. When viewed up close, it is a chaotic array of colors, but when viewed from a distance, it miraculously merges into a harmonious light and shadow. Each color dot is a note, playing a chord of colors in the viewer’s eyes.

Light and shadow are the invisible directors of painting, controlling the emotions of the picture with the rhythm of light and dark. The chiaroscuro technique is like a suspense drama. In The Supper at Emmaus, Caravaggio let a strong beam of light shoot in from the left side of the picture, illuminating the disciples’ astonished faces, while the background sinks into thick darkness. This strong contrast instantly gives the ordinary dining table a sacred ritual sense. The shadow here is no longer a redundant foil but a part of the story, hiding untold secrets.

The highlight technique is the finishing touch in the drama. The silverware in Dutch still lifes always has a dazzling pure white, which is the highlight deliberately retained by the painter, like a suddenly turned-on spotlight, instantly giving the cold metal a reflective texture. When Rembrandt painted pearls, he would dot a little lead white on the dark brown background, and that tiny light spot seemed to be really the light jumping on the surface of the pearl, instantly giving life to the still life. This technique seems simple, but it requires extreme sensitivity to light. A single wrong stroke will lose the real luster.

Texture is the most private language of painting, telling the intimate contact between materials and tools. The scraping technique is like an essay full of frustrations. In Guernica, Picasso used a palette knife to scratch deep marks in the wet paint, revealing the underlying ochre color. Those broken lines are like the cracks after a bomb explosion, filling the picture with violent tension. This technique breaks the smooth surface of the painting, making the “wounds” of the canvas a 出口 for emotions.

The rubbing technique carries accidental poetry. Artists dip leaves in paint and print them on paper, and the veins of the leaves become the protagonists of the picture; or spread the canvas on a rough wall and rub it, allowing the traces of time to naturally penetrate. These randomly generated textures carry the codes of nature, appearing more real than deliberately depicted patterns. Just as Giacometti’s sculptures retain the traces of the mold, the rubbing in painting also allows viewers to see the clues of the creative process, narrowing the distance between art and life.

These painting techniques have never been isolated skills but the way artists view the world. When we stop in front of a painting and recognize the decisiveness of outlining, the tenderness of gradation, and the passion of impasto, we are having a dialogue with the artist across time and space. After all, what really moves us is never the sophistication of the techniques, but the sensitive heart that perceives the world, hidden behind these techniques.